When I was at North Ninth Street school, we were herded off to the nurses’ office for blood tests, after which we were issued dog tags stating our names and blood types. We didn’t ask why, nor did our parents. We were all oblivious to the chilling implications. Instead we kids argued about which blood types were superior to others. My mother, in an uncharacteristically liberal frame of mind, bought me an educational record featuring songs about intolerance. One in particular tackled the sensitive subject of blood type discrimination head on. England, China and Alaska, Mexico and Madagascar, anywhere you point your finger to—there’s someone with the same type blood as you. Nevertheless, I secretly believed that O positive was the coolest of them all.

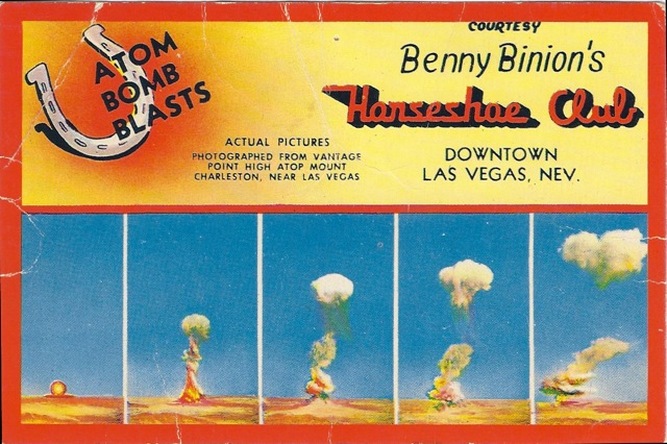

Locals were fascinated with the bomb tests. Families would drive out and park as close to the bombsite as possible to watch the sky light up. Las Vegas was booming from bombing! People came from all over the world to watch the bomb tests from hotel roofs while sipping Atomic Bomb cocktails. The Hotel Biltmore had a Miss Atomic Bomb contest, and local beauty salons featured mushroom cloud hairdos. My mother was overjoyed. She predicted that, as our first respectable industry, the Atomic Energy Commission would be the best thing that ever happened to Las Vegas. It would attract a higher class of people. Casinos would no longer dominate the landscape. There would be art museums, symphony halls, theaters. In the meantime, sidewalks on Fremont Street were littered with glass from the impact of the explosions. Greedy shop owners collected the shards in barrels, and sold them as atomic bomb souvenirs.

Las Vegas High students were bussed to the test site where they observed three little wooden houses with mannequins inside depicting quintessentially domestic scenes, such as mom in apron feeding baby in high chair with proud papa looking on. I suppose it was a modern version of the Three Little Pigs and the big bad wolf, only this time the pigs were people and the wolf was a bomb. An unusually high number of military personnel at the test site would later be diagnosed with cancer as a result of exposure to radioactivity. Downwind of the tests, small towns in Utah would report disturbingly high instances of Leukemia, especially in old people and children. Cattle and livestock would fall ill and die. All the while, kooks with Geiger counters roamed Las Vegas streets clicking their tongues about fallout. My mother called them “dirty commies.”

There were commies everywhere, especially on TV. We watched “I Led Three Lives,” and “I Was a Communist for the FBI.” Everyone was suspect. I tried to get my friends to help me spy on suspicious looking individuals and report them to the FBI, but they were chicken. I imagined receiving a medal of commendation from President Truman for ferreting out ruskie spies. My mother, too, had visions of becoming a hero. She signed up to be a “sky watcher” on the roof of the fifteen-story Fremont Hotel. Because Las Vegas was so close to Yucca Flats, it was feared that the Russians considered us a prime target. Against his better judgement, my father drove my mother to night classes on identifying enemy planes at Las Vegas High School. I was impressed with her dedication to the cause of freedom. And she wasn’t the only patriot. The class was filled to capacity. The day of the first sky watch, my mother got up early and fixed her lunch so my father could drop her at the Fremont on his way to work. She came home in a rage. It seemed she was the only sky watcher who showed up on the Fremont roof. The others had been seduced by the slot machines in the casino on the first floor. My disillusioned mother turned her back on the cold war and took up canasta.

I was relieved when President Kennedy banned above ground bomb tests in l961, even though Las Vegas experienced a downturn in tourism. The casinos lost money. My father called Kennedy a “goddamned son-of-a-bitch.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed