Tallulah Bankhead and Jack Entratter bury the time capsule (1953) Oh, how Las Vegans loved their hotels! Other cities had their sandy beaches and historical museums and monuments, but we had palaces out in the desert with casinos and show rooms. We took pride in those palaces. Along with Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, we showed them off to relatives who thought there was nothing in Vegas to brag about.

At the beginning of the fifties, there were only four hotels on the Strip, but in the next ten years there were eight more, each more luxurious than the last. The Sands stood out from all the rest. In December of l953, they buried a twelve foot rocket-shaped time-capsule at the Sands to commemorate the hotel's first birthday. It had my name in it. Along with all the names of the Las Vegas High class of l953. Jack Entratter, Sands impresario, included his daughter Caryl and her LVHS classmates in the capsule, along with Ray Bolger's dancing shoes, a wax impression of Jimmy Durante's nose, an autographed headshot of Tallulah Bankhead, Bing Crosby's pipe, Sugar Ray Robinson's boxing gloves, and a transcript of Louella Parson interviewing Sinatra on her radio show. The Sands wasn't the only hotel with a time capsule, but none of the others were quite as apropos. The Sands was short for "the sands of time," which conjures up Peter O'Toole riding a camel in the midst of a vast, eternal desert in "Lawrence of Arabia." I fantasized that in a couple hundred years someone from the future would unearth our time capsule and marvel at its contents. They'd see our names and wonder who we were and why we were in there. The Sands would still be there, glamorous and relevant as ever. As long as there was a Las Vegas Strip, there would be a Sands Hotel.

I loved the Flamingo, not only because my Uncle Bugsy had built it, but because it has the world's coolest swimming pool. Referred to as a "scalloped" swimming pool because of its sunken curves, each one filled with a smooth marble surface, l liked to slide on them in between swims. I also liked the palm trees, and the olive trees on the grounds, unique only to the fabulous Flamingo.

The El Rancho was nice, if you liked the old west, as was the equally rustic Last Frontier. I preferred the Thunderbird. It was homey. With lots of Navajo rugs and paintings, and a small casino where guys I remembered from high school were dealing cards or commanding the blackjack tables. They tended to give a girls the once over as if they were headless bodies. The intimate Thunderbird showroom hosted such popular show biz personalities as the Mills Bros., Rosemary Clooney, the McGuire Sisters, The Ink Spots. They even featured the folkies who made "Goodnight Irene," a hit, The Weavers. On the way home from the show, as I gushed about Pete Seeger and Ronnie Gilbert, my mother exclaimed: "They're goddamn Commies! Even the woman!"

In l950, the Desert Inn became the fifth hotel to adorn the LA highway. If I had to describe the DI in a word, it would be "inviting." Not that it wasn't glamorous, but the DI felt like somebody's luxurious, western style home, not a hotel. That somebody was Wilbur Clark, who ran the show at the hotel and, according to my father, was a "front" for a bunch of mobster/investors who didn't dare show their faces in Vegas, or anywhere. Everybody, especially celebrities, loved Wilbur's place. Steve Diamond, whose father was part-owner of the Silver Slipper across the street, told us a story about Howard Hughes. It seems Hughes stayed at the DI in the 60s, much to the chagrin of the management. (He hated gambling.) Annoyed by the Slipper's sign, a neon shoe that tilted back and forth all night as he tried to sleep, Hughes demanded the manager turn off the sign. The manager refused. So Hughes bought the place, and when the management at the DI finally asked him to find another hotel, he bought the DI as well.

My "fondest" memory of the DI was when I was fifteen and saw beautiful Linda Soskin and her friends in their bathing suits sipping lemonades at the pool. Linda called a waiter and signed for the drinks. Not only could she invite friends to swim, as if the pool were hers, but she didn't even have to pay for drinks! I, on the other hand, had to pretend to be a hotel guest just to dip one toe into that pool!

The Sahara opened in l952. My relatives from Cincinnati stayed there whenever they came to town. My dad used to take me there for birthdays when I was in my early teens. They had heavenly frozen éclairs. The Sahara was a classy place, but less "inviting" than the DI, and less homey than the Thunderbird. I loved the huge coffee shop, with the best ice cream sundaes in town. In the mid to late fifties, the Sahara became known for its lounge acts, Don Rickles, Louis Prima and Keely Smith among them. I once won a talent contest in Phoenix and one of my prizes was a weekend for two at the Sahara. I never took advantage.

In December of l952, the Sands, "A Place in the Sun," became the seventh luxury hotel on the Strip. Before the Sands, there was a classy restaurant, La Rue, where my parents took me for special occasions, and where I learned to make salad dressing from a nice waiter who made our salad by our table. The Sands became the "in" place in Las Vegas. Everybody cool hung out there: Sinatra and the "Rat Pack," Ella, Danny Thomas, Red Skelton. I once stood next to Kim Novak in the ladies room as she applied lipstick.

Even after other hotels sprung up on the Strip, the Sands retained its reputation as coolest of them all.

In l955, the nine story Riviera opened. My high school boyfriend got a job there as an elevator operator. His dad, who knew his way around the gambling world, told him to stay away from the mobsters. "Don't ever let them know your name." One of the big bosses noticed my boyfriend in the elevator and started asking him questions. Mayer quit the next day! I didn't like the Riviera, even though they had great shows. It was too tall.

After the Riviera came a bunch of insignificant hotels: the Hacienda, best known for its "all you can eat" brunch; the Dunes, where an exciting young choreographer put together fabulous lounge shows. One in particular has a permanent place in my memory. It was Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. While the narrator related an x-rated version of Snow White, the dwarves lined up on the stage wearing pillow case costumes that transform your whole body into a giant face. I'd seen them many times before at Vegas High assemblies, but these were different. The eyes were breasts. At first, I couldn't figure out what the mouths were. Then, Oh my god!

The Tropicana was my favorite hotel, all by itself, way out past the Flamingo. It had a beautiful pineapple sculpture in front that set the tone for the tropical theme. More than any of the other hotels, the Trop exuded glamour, elegance, sophistication, class. I saw one of my favorite shows of all time at the Trop starring Carol Channing. She did a brilliantly funny parody of Marlena Dietrich singing "Falling in Love Again." Dietrich, who was performing at another hotel, sued! She lost.

Then there was the Stardust. People even complained about it when it was going up. Garish, vulgar, crass. An embarrassment! More rooms than any place else on the Strip, the biggest parking lot in town, and the Lido de Paris, with women in g-strings, painted gold, coming out of the ceiling chained to columns and hanging above the tables during the show.

The oldest hotel on the Strip, the El Rancho Vegas, burned down in the nineties and was never rebuilt. Nobody cared about history. It was an omen. In l993 they blew up the Dunes. Big deal. It wasn't one of my favorites. When the Stardust suffered the same fate, I said "good riddance." Nor did I mourn for the Hacienda and the Aladdin. But I was shocked and saddened to learn about the Desert Inn and the Sahara.

And then they blew up the Sands. My first response was "How could they?" It was gone, obliterated, as if it never existed, to make way for the Venetian. Out with the old, in with the new.

There's not much worth keeping in Las Vegas. Nothing is real. But the Sands was an exception. It defined a whole era. All of the brilliant performers that graced its stages are gone, too. Were they still here, they would be as appalled at the Sands' demise as I. I never found out what happened to the time capsule. I read somewhere that it's under the Venetian. Another source has it buried in land fill out in North Las Vegas, like a piece of junk.

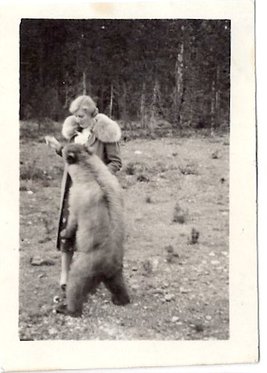

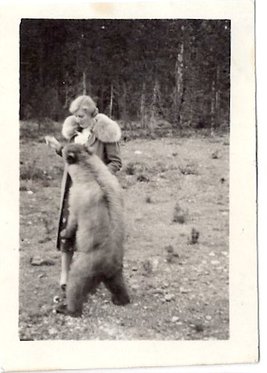

Sara on her honeymoon at Yellowstone. My mother never called my father by his first name. He was always “Sharnik." I used to call him "Big Irving of the California Club," (the joke being he was little, and a lowly cashier) but never to his face. I never saw my parents touch, but I knew from the way he looked at her, and laughed at her jokes that he was crazy about her. She merely tolerated him. When Mother served dinner, she always served me first. Big Irving’s meat would still be in the toaster oven. Burning. He'd complain that she never burned my food, as usual referring to me as "the kid." She’d tell him to make his own damn dinner. When we all went out to eat, he'd park and take off without us. By the time we joined him he'd be deep into his menu. He'd refer to the waitress as “toots!” If the lights were low for romantic effect, he’d yell, “Turn on the goddam lights!” After dining, he would floss his false teeth with a matchbook cover while perusing the check. I used to pray I was adopted!

When I was a little kid, my mother and I would walk all the way from North Ninth Street to the pawn shop on Third St. to scour the window for my father's sapphire pinky ring. If we spotted it, she'd give him hell when he got home. He often spent the night on the couch with the plastic cover. There came a time when the ring was neither in the window or on his finger, and Mother had to go to through his night table and his pants for markers—aka IOUs. When I turned thirteen, we sold the house on North Ninth for less than we'd paid to cover his gambling debts and keep the mob at bay.

Irving had a penchant for making bad investments. From the time we moved in, the house on North Ninth Street steadily decreased in value. Location, location, location. To make matters worse, the painters Irving hired disappeared with our deposit before they even started the job. Then there was the time Irving cashed in Mother's General Motors stock, a gift from her brother Harry, and invested in Edsel, which went bust. Irving spent many nights on the couch for that one. Mother didn’t have a head for business, either. Irving wanted to buy land on the Strip when it was selling for twenty-five bucks an acre. Mother nixed it—said it would never amount to anything. She called him nuts for saving silver dollars. They doubled in value. Twice as much money to blow on the crap tables! When Dean Martin sang "Money, burns a hole in my pocket," he was singing it for my parents.

When I was fourteen, Mother moved out of their bedroom into mine after Irving disappeared on a gambling binge. “I’ve had it with that S.O.B." We became roommates. Irving became “the boarder.” At first I enjoyed her company. For a prude, she had a raunchy sense of humor. But she lost it after I started dating. I hated coming home to cold cream, curlers and cross-examinations. And I didn't like hearing her go on about my dad. I was definitely on her side, but I couldn't help feeling sorry for him. She treated him like dirt. He put up with it because he loved her.

In my early twenties, I decided it was Mother's fault that Big Irving and I weren't close. She'd raised me as if she were a single parent—in fact, I began to suspect she had chosen him in order to have me all to herself. When she went to Cincinnati for two weeks to have her gallbladder out, I invited Irving to a dinner show at the Flamingo. His face lit up. He seemed genuinely touched. In the meantime, he asked me to drop him off on Fremont Street near the California Club, promising to be home on time for dinner. He didn't show his face again until Mother came home, two weeks later. For the first time, I understood what it must be like to be married to a gambler.

"Nevada's First Atomic Bomb" float. Courtesy of UNLV Special Collections _ Las Vegas wasn't a great place for kids when I was growing up. Outside of the city limits there was Lake Mead, Red Rock Canyon and winter sports at Mount Charleston, but in Las Vegas proper, most activities revolved around adults. Specifically, adults who gambled. Kids were a pain in the neck. Case in point: I was six years old when my parents made me wait outside the Golden Nugget while they gambled. Every so often my mom would wave to me through the glass. It didn't help. I felt like an orphan. A few years later, at the Last Frontier, I saw a sign by the slot machines: NO MINORS ALLOWED. I was outraged. Why couldn't those poor men who slaved in the mines play the slot machines? I expressed my concerns to my mother who explained that MIN-ORS referred to children. Like me! I felt the awful sting of discrimination, and wished we'd never left California. But for three days each May, Las Vegas pulled out all stops for a splendid celebration of the old west, not only for tourists but for the whole family. Helldorado started out as a tourist attraction in the l930's, right after Boulder (Hoover) Dam was built, and was such a hit it kept on going. In l946 here was even a Roy Rogers/Dale Evans movie named 'Heldorado," filmed on location. (The producers left out the extra "L" because they didn't want HELL to appear on marquees!)

During the festivities, Vegans were encouraged to dress up in western clothes, and most went all out. My parents chose not to, of course, but I had a red cowboy hat and a fringed vest, and a holster with cap pistols that I proudly wore to the parades. In addition to three days of parades (kids, old timers, and beauty) there was a rodeo, and a variety of contests such as "best whiskers," "best float," and Helldorado queen; a Kangaroo Court; and a full-scale carnival at Cashman Field. My parents didn't care about the kids' parade, but they dragged folding chairs three blocks to Fremont Street to watch the beauty parade, which was my favorite, as well. Luxury hotels, like the Sahara, the Desert Inn, and the Sands would spend a fortune to win "best float." The crowd cheered and whistled as the floats passed by, one more extravagant than the next, adorned with smiling bathing beauties in skimpy bathing suits and high heels. In fourth grade, Miss Olive taught us to square dance so we could dress up like pioneers and dance at all the intersections for the kid's parade. I hated my bonnet, which made my head sweat, and my long, cotton skirt that got tangled up in my legs, and I detested the corny, twangy western music. Not only was I forced to make a fool of myself in front of the whole town, but I couldn't even watch the parade. Royce Feour, a(n) friend from Fifth St. Grammar and Vegas High, remembers dressing up like a pioneer at age eight and pulling his big sister, also in costume, in their red wagon, which their talented dad had turned into a miniature covered wagon. All that effort, and they still didn't win anything. Neither did Miss Olive's square dancers, which was fine with me. There were marching bands from all over Nevada, and rows of majorettes flipping batons and catching them with one hand. There were fat dudes in fancy cowboy suits and ten gallon hats, on saddles festooned with silver, waving to the crowd like politicians, making their poor horses prance and bow, and leaving piles of horse shit all over the street. I was always curious about the Kangaroo Court. I was told, it was an evening activity for grownups that took place in the streets of Glitter Gulch. People would volunteer to be tried for bogus infractions, and be sentenced to stand in a cage to be subjected to ridicule. Nobody minded. It was all in good fun, and most of the participants were too drunk to take offense. I never convinced anybody to take me to the rodeo, but I did get to the carnival, which I loved. But most of all, I loved the parades. It wasn't just the spectacle, it was standing in a crowd made up of people from our neighborhood—people I saw every day, but barely knew, and all of a sudden we were laughing, and cheering together. It was a feeling of truly belonging in a town where kids were constantly being told to get lost.

Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner Las Vegas may have been a small town in the forties and fifties, but it was well on the way to being "The Entertainment Capital of the World." In its infancy, a Vegas floor show consisted of a headliner, eight dancing girls, and an MC--in the case of the Ramona Room at the Last Frontier, an MC who sang: Ramona, the Last Frontier is calling you…In those days, you could see the late show for the price of a cup of coffee. My father may not have been the most devoted parent, but he took me to see floor shows. I saw most of the great comics ringside. I learned how to ride a laugh, and to milk a line. By the time I was nine or ten, my father took my girlfriends along. None of my friends’ fathers took their kids to shows, or had dinner at the hotels. I considered myself very lucky. I knew how to behave at floorshows: what to wear, when to applaud, when to laugh even when you didn’t understand the joke. My friends were in awe of me. When I ordered a frozen éclair for my treat, they followed suit, though they had no idea what it was. They were taken aback at the free hand lotion in the ladies room, but when they saw me help myself they did, too.

At the Sahara, home of the “Most American Girls in the World,” we saw Betty Hutton, aka The Blonde Bombshell. My idol. In the movies, she was best known as a comedienne but on stage she sang, she danced, she clowned, and after a standing ovation she came back in a terry cloth robe, sat on the edge of the stage, and sang her heart out for twenty or thirty minutes more. Neither she, nor we, could get enough of each other. Once, I saw her gleaming with suntan lotion at the Flamingo pool and asked for her autograph. The endless exuberance she’d had on stage was gone. She looked tired, sullen, annoyed, but I loved the way she signed her name: B with etty inside of the bottom loop. I was disappointed that the real Betty Hutton wasn't the star I had fallen in love with in movies and on stage. I promised myself I would be nice to my fans when I was famous!

Then there were the lounge shows. For the price of a drink, you could see the best jazz and off-beat comedy in America, such as the outrageous Shecky Greene, who spied a man sneaking off to the men’s room during his act, leapt off the stage, scooped the poor fellow up and carried him back to his seat. Ella Fitzgerald at the Sands lounge, Don Rickles, The brilliant Mary Kaye Trio, Louis Prima and Keely Smith at the Sahara. You didn't even have to buy a drink. You could stand outside of the lounge and see everything. For free.

I saw so many brilliant headliners at Vegas shows—Danny Kaye, Carol Channing, Milton Berle, (who was much dirtier-and funnier-than on TV), Red Skelton, to name just a few, but by far, the most brilliant and versatile performer I ever saw was Frank Sinatra. Whether his voice thrilled you or not, he knew how to seduce an audience. In the forties, he came across as a nice, Catholic boy, devoted to his wife and family. He did a short film for movie theaters in which he sang “The House I Live In,” and spoke out against intolerance. On stage, he was positively wholesome. The teen girls of America, aka "bobbysoxers," squealed and swooned and swarmed around him. Then, in the fifties, Sinatra changed his image. He turned himself into a playboy: worldly, cynical, on-the-make. His career, which had taken a nosedive, went sky high again. I was in the audience at the Sands for that first comeback show. He shuffled out with the dancers in a number about money. A wad of fake cash clasped in his hand, he stuffed bills in the dancers' bosoms, dancing with them, singing with them, flirting with them and with every other woman in the house. He was bursting with energy and talent and cheeky charm. There was nothing remotely wholesome about him now. And we loved him for it! He had divorced “Nancy with the Laughing Face,” and carried on a scandalous affair with Ava Gardner. He was about to act in “From Here to Eternity,” and win an Oscar. He had earned the right to sing, “It Was Just One of Those Things,” because he knew from experience what a love affair too hot not to cool down meant. I disapproved of his womanizing, and his shady dealings with the mob, but the moment he came on stage and caressed that microphone like it was Ava, he had all of us in the palm of his hand. He made every woman in the audience think he was singing just for her. As for the guys, they just wanted to be like him.

Once, at the Desert Inn, I was standing in the lobby when I saw Frank and Ava. It was early in the morning. She was wearing a sundress—a shmatte, as my mother would say—and I doubt she had anything on under it. Frankie was standing below her on the stairs that led to the rooms, a drink in one hand, his white dress shirt wrinkled and half unbuttoned, his tie undone. They were both barefoot. He had a silly grin on his face. Hers was sultry. They were oblivious to me, and everything but each other. I felt I shouldn’t be peering into their lives, but I couldn’t stop. I felt like an intruder in their home, but I was so inconsequential they couldn't see me.

Later on, when the Rat Pack was in full swing and Frank was newly married to Mia Farrow, they all hung out at the Sands. I heard from a friend who was a parking attendant that Frank, Mia, and the boys stole a bunch of shopping carts from Safeway on the Strip and rode them into the Sands pool. Hotel guests and management weren't happy about it, but nobody had the guts to say "no" to Sinatra. The word among strip employees was, if you were on his good side, Sinatra was the most charming, generous guy in the world. But you didn't want to get on his bad side. I was a big fan, but I resented the fact that he could do anything he wanted, including marrying a girl who was even younger than me! He had so much power. They called him the Chairman of the Board, but he was more. Frank Sinatra was the King of Las Vegas.

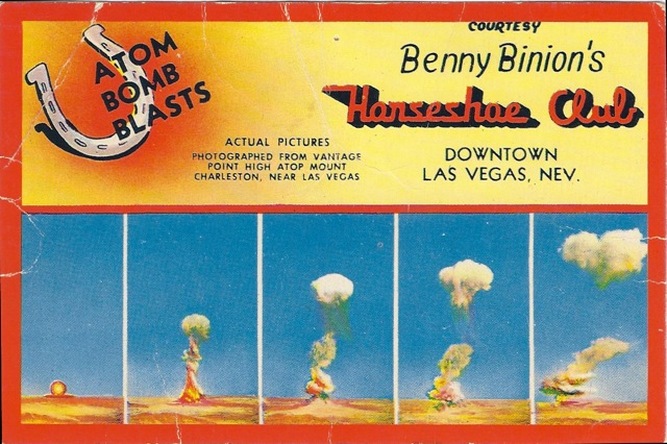

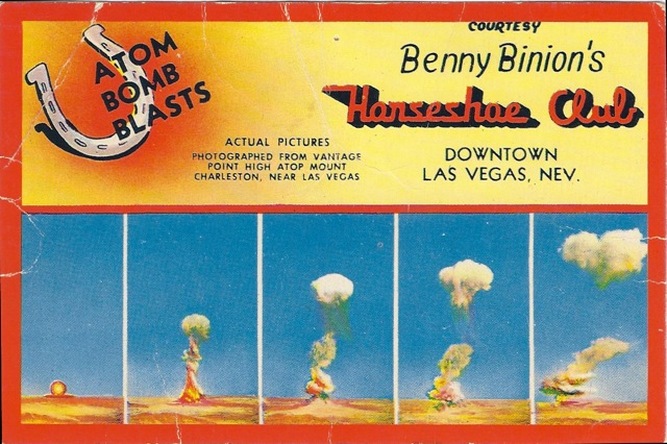

Horseshoe Club Postcard depicting atom bomb testing, circa 1950 In seventh grade, our teacher told us we were the luckiest kids in America. The above ground atomic bomb tests, at Yucca Flats, were only eighty miles from Las Vegas. We could actually feel the earth shake and see the mushroom clouds. Our teacher, who habitually drank whiskey at her desk behind a Review Journal newspaper, delighted in conducting bomb drills. She patrolled the aisles, kicking legs that protruded from under our desks. She showed us movies about Tommy the Turtle whose shell protected him from bad stuff like radioactivity. She oversaw the reading of books that told us to “duck and cover.” At John S. Park School, kids reported being pelted with greasy rain when they were in the playground. Their teacher instructed them to drop to the ground and put their arms over their heads. No one seemed to question the logic behind any of this.

When I was at North Ninth Street school, we were herded off to the nurses’ office for blood tests, after which we were issued dog tags stating our names and blood types. We didn’t ask why, nor did our parents. We were all oblivious to the chilling implications. Instead we kids argued about which blood types were superior to others. My mother, in an uncharacteristically liberal frame of mind, bought me an educational record featuring songs about intolerance. One in particular tackled the sensitive subject of blood type discrimination head on. England, China and Alaska, Mexico and Madagascar, anywhere you point your finger to—there’s someone with the same type blood as you. Nevertheless, I secretly believed that O positive was the coolest of them all.

Locals were fascinated with the bomb tests. Families would drive out and park as close to the bombsite as possible to watch the sky light up. Las Vegas was booming from bombing! People came from all over the world to watch the bomb tests from hotel roofs while sipping Atomic Bomb cocktails. The Hotel Biltmore had a Miss Atomic Bomb contest, and local beauty salons featured mushroom cloud hairdos. My mother was overjoyed. She predicted that, as our first respectable industry, the Atomic Energy Commission would be the best thing that ever happened to Las Vegas. It would attract a higher class of people. Casinos would no longer dominate the landscape. There would be art museums, symphony halls, theaters. In the meantime, sidewalks on Fremont Street were littered with glass from the impact of the explosions. Greedy shop owners collected the shards in barrels, and sold them as atomic bomb souvenirs.

Las Vegas High students were bussed to the test site where they observed three little wooden houses with mannequins inside depicting quintessentially domestic scenes, such as mom in apron feeding baby in high chair with proud papa looking on. I suppose it was a modern version of the Three Little Pigs and the big bad wolf, only this time the pigs were people and the wolf was a bomb. An unusually high number of military personnel at the test site would later be diagnosed with cancer as a result of exposure to radioactivity. Downwind of the tests, small towns in Utah would report disturbingly high instances of Leukemia, especially in old people and children. Cattle and livestock would fall ill and die. All the while, kooks with Geiger counters roamed Las Vegas streets clicking their tongues about fallout. My mother called them “dirty commies.”

There were commies everywhere, especially on TV. We watched “I Led Three Lives,” and “I Was a Communist for the FBI.” Everyone was suspect. I tried to get my friends to help me spy on suspicious looking individuals and report them to the FBI, but they were chicken. I imagined receiving a medal of commendation from President Truman for ferreting out ruskie spies. My mother, too, had visions of becoming a hero. She signed up to be a “sky watcher” on the roof of the fifteen-story Fremont Hotel. Because Las Vegas was so close to Yucca Flats, it was feared that the Russians considered us a prime target. Against his better judgement, my father drove my mother to night classes on identifying enemy planes at Las Vegas High School. I was impressed with her dedication to the cause of freedom. And she wasn’t the only patriot. The class was filled to capacity. The day of the first sky watch, my mother got up early and fixed her lunch so my father could drop her at the Fremont on his way to work. She came home in a rage. It seemed she was the only sky watcher who showed up on the Fremont roof. The others had been seduced by the slot machines in the casino on the first floor. My disillusioned mother turned her back on the cold war and took up canasta.

I was relieved when President Kennedy banned above ground bomb tests in l961, even though Las Vegas experienced a downturn in tourism. The casinos lost money. My father called Kennedy a “goddamned son-of-a-bitch.”

Fifth grade girls at the Boulder Dam In fifth grade, we all had to transfer to Fifth Street School, where I had attended first grade when we lived on Bonneville Ave. That’s when I met my first rich Mormon. Her name was Alice, and she had shiny braces like Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet. I’ll say one thing for Alice, she had presence. When called upon to read aloud, she stood, nose in the air, and recited in flawless prose, with a slightly English accent, obviously inspired by Miss Taylor. No one else in class came close to her except me, with perfect diction acquired from elocution lessons at Jeanne Robert’s School of Dance. Perhaps that was why she hated me? On the first day of school, Alice wore a starched blue dress with tiny white dots, a white, lace-trimmed collar and a bow in back. It was definitely the nicest dress in class, except for mine. When our eyes met, hers were not only haughty, but vicious. I knew she would make my life miserable.

At lunchtime, all of the girls would gather on the front steps. On either side of the landing were secluded areas where one could perform in privacy before a select audience. Alice’s admirers cheered her on as she acted out boring little vignettes about her family and her pets. She clearly thought she was brilliant. I, on the other hand, was content to practice my tap dancing alone on the other side of the steps, which Alice must have found annoying. In front of her friends, she made a point of asking if I were still going to dancing school, as if it were something one outgrew. Not only was I still dancing, I replied, but I was preparing for a solo performance in which I would be wearing a pink satin costume trimmed with maraboo. Alice shot me a withering look. “I take piano lessons,” she said.

Deryle Ann was no longer my best friend. She had shifted her loyalty to Alice who merely tolerated her because they were both Mormon. Thus it was, that my only friend that year was Helen the hairlip. Helen had stringy blond hair that she never combed, and wore unflattering clothes over her lanky, awkward, boney body. She also picked her nose. Worst of all, she had a habit of coming up behind me and smacking me hard on the back. Even though I threatened to kill her for it, she was apparently willing to take the risk. Helen and I gravitated toward the same movies. While many of our classmates preferred Bogey and Bacall, we liked Abbot and Costello. We also enjoyed playing dress-up in our mothers’ old clothes. Other than that, we had little in common but shared humiliation at the hands of Alice and her cohorts.

Toward the end of the school year, Alice seemed to lose interest in tormenting Helen and me. I was relieved. With my father struggling to make ends meet, and my mother threatening to divorce him, I had enough to deal with. Then, Alice’s sidekick, Elaine, offered me a ride home on her bike. Elaine and Alice were very close, despite the fact that Elaine’s parents were only middleclass, and Protestant. Tomboyish, with short brown hair and a chubby face, Elaine was popular with boys. She was probably the smartest kid in class. And the cleverest. Why she liked Alice was beyond me. We had just passed the El Cortez Hotel when she asked me what boy I liked? I didn’t know what to say. Boys didn’t interest me, and I definitely didn’t interest them! I lied and said Gordon Stewart, a freckle-faced kid who dressed like a hick, but was good at multiplication like me. Elaine teased me about Gordon the rest of the way home, but in a nice way. I couldn’t figure out why she was acting like we were friends. Then, I got a call from Deryle Ann. She said Alice and Elaine were going to invite me and Helen to a party. They were starting a Special Girls Club for us. I suspected there was an ulterior motive behind it, but Helen was giddy with gratitude.

Deryle Ann’s father drove Deryle, Helen and me to Elaine’s house for the party. We sat on the couch drinking Seven Up, waiting for Alice. Elaine attempted to engage us in conversation, but her flushed cheeks and shifty eyes told us something was wrong. After an interminable 45 minutes, Elaine left the room to have a private chat with Alice on the phone. She came back with a long face. It seemed Alice couldn’t make it because she was too busy and we’d have to reschedule, but she couldn’t promise that she’d ever be free because she was just so busy. Helen was fighting back tears. I squeezed her hand. It was bad enough to treat me like a nobody, but Helen had enough to contend with without this. Deryle Ann called her father to come get us. Later on, she told me the truth. Alice and Elaine had felt bad that they had been mean to us all year, and wanted to teach us how to be popular, like them. They planned to show us how to do our hair, what to wear, what to say, and how to act around boys. They were even going to recommend foundation makeup for Helen’s deformity. Weren’t they just the nicest girls?

In third grade, I met Deryle Ann Arnold. She was tall, tan, with big brown eyes, a pug nose, and long wavy hair. I loved her the minute I laid eyes on her. She lived in a housing project called Kelso Turner, two blocks from my house. She was Mormon. I’d never known a Mormon. Her mother and father wore creepy underwear called garments. They were always hanging on the clothesline when I went over to her house. Kelso Turner was for poor people. All the houses crowded next to each other. The Arnold’s clothesline overlapped with the lawn of their next door neighbor’s. The floors were smelly linoleum. The rooms were tiny. But the Arnolds didn’t seem to mind being poor. Mrs. Arnold was pretty, like Deryle Ann, but overweight. She said quaint things like, “Oh, my stars and garters!” Deryle Ann, who was pleasingly plump, shared a room with her spoiled sister, Shirley, slim, with curly brown hair, and incompetent at housework. Deryle Ann had to do most of the chores in addition to babysitting. A tenth of her babysitting money went to the church, which I thought unfair, but Deryle Ann said it meant she and her family would never starve if her father lost his job. My mother adored Deryle Ann because she was so efficient, and wished I were. Mother allowed me to go to church with Deryle Ann because there weren’t any Jews in our neighborhood. I thought it was strange that they passed around little pieces of stale bread and tiny paper cups of water during their Sunday services. I ate them, even though I suspected they had something to do with Jesus Christ. I also thought it was odd that during the service, people would stand up as if in a trance and tell how they knew Mormonism was the one, true religion. I wasn’t convinced. On my way out, I stopped to say hello to the Bishop, explaining that I was Jewish, and just visiting. He smiled, condescendingly, and said “Ah, yes, the Hebrews,” and that they were some tribe whose name I’d never heard. I had a mind to tell him we Jews had been around a lot longer than Mormons, and I’d never even heard of Mormons until I moved to North Ninth St., but I thought better of it.

Deryle Ann’s friend, Betty Lou Anderson, lived in a big house on top of a hill. Her father was in construction, and her parents had built their house themselves. Betty Lou’s mom didn’t wear makeup, not even lipstick. With her wire-rimmed glasses like my grandmother’s, she looked like a pioneer woman in blue jeans and moccasins. Her pantry was stocked with hundreds of jars of fruits and vegetables. “For the end of the world,” she told me, adding that they were just for Mormons; even if I were starving I couldn’t have any unless I converted. I didn’t say it, but I thought I’d rather starve. Betty Lou was one of those girls who seem to know everything, especially about sex. In fifth grade, she told Deryle Ann and me that to get a baby you had to let a man put his thing in you, which hurt so bad most women couldn’t stand it more than a minute or two. “It’s twenty minutes for twins,” she said with a solemn, know-it-all face. Even worse, she told us that her twelve year old cousin was getting married as soon as she got her period to a sixty year old man who already had fifteen wives. I almost puked over that one!

In a way, North Ninth Street was similar to Bonneville Ave. We were hardly rich, but compared to most of our neighbors we were rolling in dough. The first year we lived there, mother threw a birthday party for me and hired a woman in a maid’s uniform to help. Mother even had a grab bag full of games for kids who didn’t win a prize at Pin-the-tail-on-the-Donkey. My birthday party was talked about for years. Which was fine in second grade, when Mrs. Fife told the class I had the highest score on the second/third grade achievement test, and in third grade when I was the teacher’s pet. But in fourth grade, I had Mrs. Olive. She hated me. And the more she hated me, the more my classmates followed suit, even Deryle Ann. They had all resented me since the birthday party, and this was their chance to show it. My mother tried to make things better. She had a little talk with Mrs. Olive. It seems Mrs. Olive wanted me to wear jeans like the other kids instead of fancy dresses from a children’s store in Hollywood. My mother said she didn’t pay good money for my clothes so they could rot in the closet. Then, to make matters worse, she asked why my grades had fallen when I was one of the brightest children at North Ninth St. School? I was screwed! Mrs. Olive would ask me to tell the class what grade I had received on the history test. “C,” I’d say, and she’d say, “And your mother thinks you’re bright.” She took to throwing erasers at me when I wasn’t paying attention, which was often. She would stand over me when I was taking a exam, so close I could feel her hot breath on my neck. I vowed to myself that I would buy a gun and shoot her through the head when I grew up.

“How could you flunk kindergarten?” My mother asked without attempting to hide her disgust as we walked home to our apartment in Los Angeles. We had just had a conference with my teacher who thought I should repeat kindergarten because I was a slow learner and couldn’t tie my shoes, a priority for entering first grade in California. “At least you’re pretty,” Mother said. When we moved to Las Vegas, where standards were surprisingly higher, she assumed that I would be held back. At Fifth Street School, my teacher, scowling Mrs. Anderson, patrolled the aisles, keys clanging, making sure none of us were cheating on the standardized test. She stopped when she reached me. I was looking straight ahead, seeing nothing. My teeth were chattering. I hadn’t even picked up my pencil. ‘Follow me,” she ordered. She frowned as she read me the questions in her office, but smiled when I got them right. I will never know how she sensed what I needed, or why she decided to help me. To my mother’s astonishment, I was placed with Mrs. Dordey in high first where I was one of the best readers in my class.

The frame house in the vacant lot behind our apartment on Bonneville Ave. was falling down. There was a huge hole in the porch. All the front windows were smashed. Mother went out of her way to make friends with the poor people who lived there, because she needed babysitters and they had six daughters. Beverly, 16, became my principal babysitter. She used to request songs on the radio and dedicate them to her boyfriend. I couldn’t wait to be old enough to do that. Virginia and Linda, closer to my age, were hired to walk me the two blocks to Fifth Street School, and home when school was over. As far as I knew, I was the only kid in first grade whose mother thought she couldn’t walk to school on her own. I liked Virginia and Linda, but they smelled. I hated and feared some of my classmates. I wasn’t the only one. Poor Arlyss Bishop, who glowed with goodness and whose blonde hair was so pale it was almost white, was terrorized by a boy who tried to kiss us both. Arlyss and I would cling to each other in the bushes, hiding until the bell rang. And the class bully, Rickey Woodbury wouldn’t let me get off of the merry-go-round until I begged, and punched me in the stomach to make me cry, but I clenched my teeth and stared him down.

Mother gave Virginia my worn out shoes when hers fell apart. Otherwise, she’d have had to go to school barefoot. We were hardly rich, but next to them we might as well have been millionaires. By the end of first grade my father had found a house. My mother had wanted to move to Huntridge because she heard that most of the respectable Jewish families were settling there, but my father objected to the cement floors. Plus, they didn’t have sidewalks. Despite my mother’s objections, we bought a house at 328 North Ninth St. because it had hardwood floors, but you could see the bathroom from the living room. Mother made the best of the situation and decorated in Chinese Modern. She was right. Doctors, dentists, lawyers, even rabbis settled in Huntridge, and I was the only Jewish kid at North Ninth Street School.

After Bugsy died, my father never had another chance at the big time, but he was still in the thick of things, so much so that he attracted the interest of Senator Estes Kevfauver’s Senate Crime Committee when he was head cashier at the California Club. He came home all excited about a free trip to New Orleans courtesy of the US government—a vacation, he called it. Some vacation. Two tough guys in suits greeted him at the airport and led him onto the plane in handcuffs. In New Orleans, he was blindfolded, taken to a bare room, cuffed to a chair, a bright light shining in his eyes, and grilled all night. “They treated me like a criminal.” Even so, he found time to buy me a pale blue cashmere sweater. Guess being handcuffed brought out his sentimental side.

Post Bugsy, the only real contact I had with “mobsters” was through the Las Vegas Jewish Community Center. Even though I wasn’t really part of their crowd, I was occasionally invited to birthday parties. Ruby Kolod was part owner of the Desert Inn, one of my favorite hotels. He had a big family—four or five kids. His daughter’s party wasn’t a fancy hotel shindig like many of the others I’d heard about. It was a barbeque at his lovely, unpretentious ranch-style home, and he was the cook. I will always remember Mr. Kolod serving up hotdogs, covered with kids, laughing and tickling and having a grand time—a real teddy bear. I wished he were my father! My mother claimed he murdered half of Chicago. The Green Felt Jungle wasn’t especially kind to him, either. In my mind, he was a mench.

There’s a tendency to think the worst of anyone even remotely connected to the mob. In high school, one of my friends dated Toby Gordon, whose father was rumored to have been a hit man in Miami. He said every time Mr. Gordon looked at him he felt he was being sized up for a coffin. Obviously, an over-reaction. One of my old boyfriends told me about a job he’d had as an elevator operator at the Riviera. He recognized a couple of the mobsters as they got on. Not the nice guys, like Ruby Kolod. The ones with ice in their eyes who never smiled. Occasionally, they’d say something to him. “What’s your name, kid?” His dad, who worked in the casino, told him, “Don’t let them know who you are.” He quit the job.

On the other hand, living in Las Vegas can give you a distorted view of reality. I never questioned why people had names like “Bugsy,” and “Three fingers,” until I went away to college and it dawned on me that these were not normal people! My dad was so immersed in his own little world that he had completely lost touch with reality. I took a course in criminology in college and brought home a list of America’s ten most wanted. My dad saw it on the coffee table and picked it up. Not only did he know all of them, he knew where they were! “Oh, yeah, I seen him at the Nugget the other day. Nice guy.”

When I was seven we took our first California vacation since Mother and I moved to Las Vegas. My father had won some money gambling, and he had all the time in the world after Bugsy died, so he proposed a vacation by the ocean in Del Mar, near San Diego. Mother bought me a new bathing suit, and a beach ball. We got up in the middle of the night to beat the heat. Cars weren’t air-conditioned in those days. Some people attached their swamp air-conditioner to a car window. Others covered the windows with cool rags. We bought a big plastic bag with ice chips to throw under the hood if the car over heated. Del Mar was a ten hour drive, even going ninety when there were no speed limits. We hoped to be well past the California border by the time the sun came up.

During the first part of the trip, I slept, head on Mother’s lap. It was pitch black out. When I woke up the sun was shining. We were in California, near Baker. We had just passed the road to Tehachapi Women’s Prison, Mother told me. It worried me to think that women could be imprisoned just like men. I hoped that would never happen to me. The towns in this part of California were so small they listed their populations on signs at the side of the road. “Why in the hell would anybody live here?” My mother asked in Baker. We stopped to have a coke and use the bathroom at a restaurant on Main Street. In the Ladies Room, the stalls were divided into pay and free. It cost a nickel to use the fancy toilet that smelled of pine disinfectant. Mother persuaded me to crawl under the door and let her in after I peed. The exotic toilet seat hummed, and gave off a purple glow, and felt warm on my bottom. Definitely worth the price! I unlocked the door for Mother. As we passed through the doorway, I saw a woman, staring at us disapprovingly. My face heated up with shame. What if she told the boss of the restaurant? Would we end up in Tehachapi? My parents ordered us cokes at the old fashioned soda fountain with the antique cash register. I wanted to use the bathroom again, but I refused to crawl under the door and Mother said the free toilets were full of germs. We stopped for gas at a town whose name I can’t remember. “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.” I hated when my father referred to his car as a woman.

The next part of the trip was my favorite. I sang every song I knew, and some I barely knew, at the top of my voice. My parents smiled. I think they were grateful that they didn’t have to talk to each other. I especially liked cowboy songs, and anything by Judy Garland whom I wanted to be like when I grew up. When I tired of singing, I would nap on my mom’s lap. Her cotton full skirt was moist from perspiration, warm, soft, safe. I could tell she loved having my head there. It was the closest we ever got. She didn’t feel the need to nag me. I didn’t feel guilty because I couldn’t live up to her expectations. We just bounced along in the car.

Del Mar was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. Miles and miles of white sandy beach. Dazzling flowers with ripe green leaves. A motel only steps away from the glistening blue ocean and the wide blue sky. Mother unpacked my beach ball and blew it up red and blue and yellow. I wanted to go right to the beach but she said we had to go somewhere first.

Del Mar has a famous racetrack. My father had worked there as a young man. People still knew him there. They called him by his nickname, “Cy.” He disappeared with one of them before the race. I watched the horses with my mother, but they were moving so fast they were just a blur. When we got back to the motel, my parents weren’t speaking to each other. My mother deflated the beach ball. When I asked why we were packing, my father told me to shut up. Until we reached Baker, they didn’t say a word. Then, it started. She said he was lower than a worm. He called her a goddam bitch. I was afraid they would kill each other and I’d be all alone in the middle of the desert. The bickering was affecting his driving, causing the car to lurch and weave. I was afraid we would have an accident. It was dark by then, and hard to see with all the dust. He went left instead of right. We were on the road to Tehachapi Prison. My mother yelled, “Now we’re lost! You can’t do anything right, you stupid jerk.” The wheels shrieked as he turned the car around. “Goddamn you, shut your mouth.” I thought we would all die out there in the desert, and the women prisoners would find us and tear our bodies to shreds like animals.

After we got home, my parents didn’t speak to each other for a month. The beach ball ended up in the garbage.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed