After Bugsy died, my father never had another chance at the big time, but he was still in the thick of things, so much so that he attracted the interest of Senator Estes Kevfauver’s Senate Crime Committee when he was head cashier at the California Club. He came home all excited about a free trip to New Orleans courtesy of the US government—a vacation, he called it. Some vacation. Two tough guys in suits greeted him at the airport and led him onto the plane in handcuffs. In New Orleans, he was blindfolded, taken to a bare room, cuffed to a chair, a bright light shining in his eyes, and grilled all night. “They treated me like a criminal.” Even so, he found time to buy me a pale blue cashmere sweater. Guess being handcuffed brought out his sentimental side.

Post Bugsy, the only real contact I had with “mobsters” was through the Las Vegas Jewish Community Center. Even though I wasn’t really part of their crowd, I was occasionally invited to birthday parties. Ruby Kolod was part owner of the Desert Inn, one of my favorite hotels. He had a big family—four or five kids. His daughter’s party wasn’t a fancy hotel shindig like many of the others I’d heard about. It was a barbeque at his lovely, unpretentious ranch-style home, and he was the cook. I will always remember Mr. Kolod serving up hotdogs, covered with kids, laughing and tickling and having a grand time—a real teddy bear. I wished he were my father! My mother claimed he murdered half of Chicago. The Green Felt Jungle wasn’t especially kind to him, either. In my mind, he was a mench.

There’s a tendency to think the worst of anyone even remotely connected to the mob. In high school, one of my friends dated Toby Gordon, whose father was rumored to have been a hit man in Miami. He said every time Mr. Gordon looked at him he felt he was being sized up for a coffin. Obviously, an over-reaction. One of my old boyfriends told me about a job he’d had as an elevator operator at the Riviera. He recognized a couple of the mobsters as they got on. Not the nice guys, like Ruby Kolod. The ones with ice in their eyes who never smiled. Occasionally, they’d say something to him. “What’s your name, kid?” His dad, who worked in the casino, told him, “Don’t let them know who you are.” He quit the job.

On the other hand, living in Las Vegas can give you a distorted view of reality. I never questioned why people had names like “Bugsy,” and “Three fingers,” until I went away to college and it dawned on me that these were not normal people! My dad was so immersed in his own little world that he had completely lost touch with reality. I took a course in criminology in college and brought home a list of America’s ten most wanted. My dad saw it on the coffee table and picked it up. Not only did he know all of them, he knew where they were! “Oh, yeah, I seen him at the Nugget the other day. Nice guy.”

When I was seven we took our first California vacation since Mother and I moved to Las Vegas. My father had won some money gambling, and he had all the time in the world after Bugsy died, so he proposed a vacation by the ocean in Del Mar, near San Diego. Mother bought me a new bathing suit, and a beach ball. We got up in the middle of the night to beat the heat. Cars weren’t air-conditioned in those days. Some people attached their swamp air-conditioner to a car window. Others covered the windows with cool rags. We bought a big plastic bag with ice chips to throw under the hood if the car over heated. Del Mar was a ten hour drive, even going ninety when there were no speed limits. We hoped to be well past the California border by the time the sun came up.

During the first part of the trip, I slept, head on Mother’s lap. It was pitch black out. When I woke up the sun was shining. We were in California, near Baker. We had just passed the road to Tehachapi Women’s Prison, Mother told me. It worried me to think that women could be imprisoned just like men. I hoped that would never happen to me. The towns in this part of California were so small they listed their populations on signs at the side of the road. “Why in the hell would anybody live here?” My mother asked in Baker. We stopped to have a coke and use the bathroom at a restaurant on Main Street. In the Ladies Room, the stalls were divided into pay and free. It cost a nickel to use the fancy toilet that smelled of pine disinfectant. Mother persuaded me to crawl under the door and let her in after I peed. The exotic toilet seat hummed, and gave off a purple glow, and felt warm on my bottom. Definitely worth the price! I unlocked the door for Mother. As we passed through the doorway, I saw a woman, staring at us disapprovingly. My face heated up with shame. What if she told the boss of the restaurant? Would we end up in Tehachapi? My parents ordered us cokes at the old fashioned soda fountain with the antique cash register. I wanted to use the bathroom again, but I refused to crawl under the door and Mother said the free toilets were full of germs. We stopped for gas at a town whose name I can’t remember. “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.” I hated when my father referred to his car as a woman.

The next part of the trip was my favorite. I sang every song I knew, and some I barely knew, at the top of my voice. My parents smiled. I think they were grateful that they didn’t have to talk to each other. I especially liked cowboy songs, and anything by Judy Garland whom I wanted to be like when I grew up. When I tired of singing, I would nap on my mom’s lap. Her cotton full skirt was moist from perspiration, warm, soft, safe. I could tell she loved having my head there. It was the closest we ever got. She didn’t feel the need to nag me. I didn’t feel guilty because I couldn’t live up to her expectations. We just bounced along in the car.

Del Mar was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. Miles and miles of white sandy beach. Dazzling flowers with ripe green leaves. A motel only steps away from the glistening blue ocean and the wide blue sky. Mother unpacked my beach ball and blew it up red and blue and yellow. I wanted to go right to the beach but she said we had to go somewhere first.

Del Mar has a famous racetrack. My father had worked there as a young man. People still knew him there. They called him by his nickname, “Cy.” He disappeared with one of them before the race. I watched the horses with my mother, but they were moving so fast they were just a blur. When we got back to the motel, my parents weren’t speaking to each other. My mother deflated the beach ball. When I asked why we were packing, my father told me to shut up. Until we reached Baker, they didn’t say a word. Then, it started. She said he was lower than a worm. He called her a goddam bitch. I was afraid they would kill each other and I’d be all alone in the middle of the desert. The bickering was affecting his driving, causing the car to lurch and weave. I was afraid we would have an accident. It was dark by then, and hard to see with all the dust. He went left instead of right. We were on the road to Tehachapi Prison. My mother yelled, “Now we’re lost! You can’t do anything right, you stupid jerk.” The wheels shrieked as he turned the car around. “Goddamn you, shut your mouth.” I thought we would all die out there in the desert, and the women prisoners would find us and tear our bodies to shreds like animals.

After we got home, my parents didn’t speak to each other for a month. The beach ball ended up in the garbage.

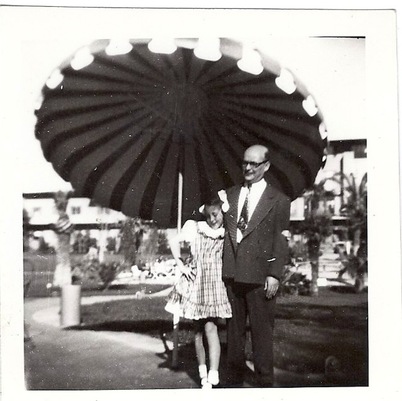

The accountant and his daughter in 1947 People my mother considered common were at the top of the order in Las Vegas. The hotels were their playgrounds. They had nicer cars, more expensive clothes, more privileges than the rest of us. And more power. Ed Reid in The Green Felt Jungle described “little Moey Sedway” as “a tiny guy with a large nose and moist, close-set eyes, who talked freely from both sides of his mouth . . . a punk . . . Bugsy Siegel’s personal flunky.” Ed Reid didn’t know Mr. Sedway the way I did. Moey hosted all of the social events for Mr. Siegel’s staff. He drove a big, black car, smoked imported cigars and had a beautiful mistress who wore mink to Friday night services, while my mother muttered “scum” under her breath, and whose daughter was in my Sunday school class. At parties, he was gracious, soft-spoken, and even playful. He had a fuzzy red bird toy that balanced on the rim of a cocktail glass and bobbed up and down. I thought he was the most sophisticated grownup I knew.

And then there was Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, my father’s and Moey’s boss. Handsome enough to be in the movies, he would bounce me on his knee and give me silver dollars for my piggy bank. My mother had a crush on him. She’d say, “Why can’t your father be more like Benny? He’s so refined.” She had no idea he’d murdered twenty or thirty people. My father probably knew, but he never said anything. He worshiped Siegel. Benny had monogrammed shirts made for him, and picked up the tab when the Sharniks from Detroit and California were in town. Irving was making good money in those days, especially after the Flamingo opened. He was promoted to head of skimming. I had no idea what that meant. I thought it referred to the skin on hot chocolate. I pictured my dad in a chef’s hat with a little ivory handled knife. What did I know?

My mother was actually happy in those days. I remember when she came home from a New Year’s Eve party at the Flamingo. She had a paper hat on. She sat on the edge of my bed and told me about the cocktail waitresses in net stockings and the celebrities and the caviar and champagne. Seven months after the Flamingo opened Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel was shot full of holes in his mistress’s house in Los Angeles. They never found out who did it. Everybody thought Meyer Lansky gave the order, but my father said he had a lot of enemies. Beldon Katleman, of the El Rancho hated Siegel’s guts. When Bugsy tried to horn in on the El Rancho, Katleman had him pistol whipped in front of everybody at the pool and dumped in the desert. Then, Bugsy goes and builds the Flamingo, like a slap in Katleman’s face.

My dad lost his job at the Flamingo. Nobody wanted to hire him because of Siegel. Finally, Moey Sedway gave him a job at the Golden Nugget as a dealer. He had been demoted. He and my mother started yelling and screaming about money again. Colliers Magazine did an article about Vegas that featured a full-page photograph of my dad dealing cards at the Nugget. The caption read: The Empty Face of Las Vegas. He thought it was a compliment. My mother and her family were mortified. Our lives might have been very different if Siegel had lived but, as I realized when I was older, we wouldn’t have been safe. In Las Vegas, you’re better off being a nobody.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed