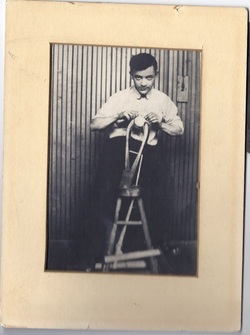

Irving, age 13, making baseballs in Cincinnati

My father only loved two people in his lifetime: my mother and Bugsy Siegel. Well, three, if you count Grandma Sharnik. I used to pray he wasn't really my father. I didn't look like him, didn't act like him. I wished he would go away. I'm sure he wished I'd do the same. Most of the time, he ignored me, except in front of other people when I was all dressed up: “Looks just like her mother.”

I couldn't imagine two people less suited for each other than my parents. He was short, swarthy, bald. She was tall and pale, with thick, dyed blonde hair. She didn't approve of gambling. She complained about his personal hygiene. For good reason. He didn't shower on a regular basis, didn't

bother with deodorant. But his fingernails were immaculate. He had them done by a manicurist on First Street. Gamblers are fussy about their hands.

My dad wasn't always a gambler. He was born in a small village near Moscow and came to America in 1900 when he was about ten, along with his parents and his three younger sisters: lovely, intelligent, classy Anne; bitter, homely, spiteful Shirley; and coarse, flea-brained, sexy Rose. The Sharniks

settled in Cincinnati, Ohio, my mother's home. They even stayed with her family before they found a place of their own, and my mom was a bridesmaid at classy Anne's wedding to dapper John Keystone from Canada.

At thirteen, my dad displayed a remarkable facility for doing complicated math problems in his head, a talent which would serve him well in the mob. He quit school after third grade because he was bored, ridiculously out of place with all the eight year olds, and found a job in a factory making baseballs. I have a picture of him sitting behind a loom, looking like one of the street kids from “The Bowery Boys.” That was the first of only two legitimate jobs he would have in his life. A few years after quitting school, he fell in with a gang of lowlifes and ne'er-do-wells who lured him across the bridge from Cincinnati to that den of iniquity known as Newport, Kentucky, where he fell in love for the first time. Her name? Farobank.

According to my mother, who heard it from my aunt Shirley, my father underwent a dramatic personality change after a business trip with his dad while in his teens. It seems his father had a mistress. Shades of “Death of a Salesman!” Shirley claimed that, after that trip, my father stopped talking and aged ten years. Then there's the story, which may or may not be true, about how my dad lost his hair at the tender age of eighteen. His sister, sexy Rose, was a leggy blonde who loved palling around with the boys. Prudish Irving disapproved. When Rose attempted to leave the house to meet her boyfriends, Irving barred the way, and a struggle ensued, during which she grabbed hold of his hair and literally snatched him bald. On the other hand, Grandma Sharnik insisted that her son's early hair loss was the result of a tongue operation when he was a baby. Nobody took her seriously.

I never met my grandfather, who died of stomach cancer a year before I was born, but my mother filled me in. He was tall, handsome, well built, articulate and a spiffy dresser. Ladies adored him. My mother often wondered aloud why he married my grandmother when she looked like a monkey and could barely speak in sentences. In all fairness to Grandma Sharnik, my aunt Ann told me she was a talented landscape painter who encouraged her children to appreciate the arts. Then again, Aunt Ann was lavish with her praise of all things Sharnik.

Sharnik, which should be Shornik but they messed up on Ellis Island--means harness maker in Russian, and was the occupation of many generations of Shornik men. As automobiles began to replace the horse and buggy, my grandfather began to look for a new profession, and eventually moved the

family from Cincinnati to Detroit to work for the Dodge brothers. After classy Anne and sexy Rose married, my grandparents and spiteful Shirley moved to Hollywood to pursue the American Dream. That dream took the form of a little nut stand tucked into a spacious driveway on Hollywood Blvd.,

across the street from Dupar's Cafeteria. Grandpa's roasted nuts became the talk of the town, beloved by movie stars and moguls. It is said that Shirley almost fainted when Errol Flynn stopped by for a bag of cashews; Grandma Sharnik told him he was so handsome he should be in the movies. The success of the nuts made it possible for the Sharniks to buy a little house on DeLongpre Ave. where Shirley planted trees and flowers in their tiny backyard, and began a lifetime obsession with parakeets, canaries and antique doorknobs. Irving, who had moved to California before them, was a

frequent visitor at their dinner table.

Eventually, Grandpa Sharnik entrusted his nuts to his wife and daughter and spent most his days philosophizing about life on the beautiful beaches of southern California, waiting until the ocean was cold as ice before plunging fearlessly into the waves. My mother said her father-in-law took to the

beaches because he couldn't stand to be around his wife. She also confided that Grandpa was a card carrying Communist, which thrilled me no end when I was a college student going through my wild-eyed radical phase. I was sad that I never knew my grandfather. I'd have loved to have sat on the beach listening to him talk about communism and capitalism and Arthur Miller.

After my grandfather died, Grandma Sharnik and spiteful Shirley bought a big store on the Boulevard and called it The Hollywood Nut Shop. Mother said they were the biggest nuts in the place. Shirley grew more and more bitter about being stuck taking care of her sickly mom while her sisters had

husbands and children and spent their days lounging around having tea and chocolates. When I was little, my mother would leave me at the nut shop while she shopped and did errands. I loved the rock candy, but Aunt Shirley scared me. I will never forget the time a lovely woman, beautifully dressed,

very refined, came in to buy a dried fruit gift package to send her husband who was overseas in the war. She asked Aunt Shirley about gift wrapping. Aunt Shirley's eyes burst into flame. WRAP IT YOURSELF! She was obviously jealous of this married woman whose brave husband was over there fighting the Nazis. Shirley thrust a role of white paper and some scotch tape at the woman. I expected her to leave without paying. To my dismay, she smiled, then did as she was told. I was shocked! I could be afraid of Aunt Shirley, I was just a little kid, but this was a grownup, and not just any grownup but a beautiful lady in movie star clothes. She should have had the wherewithal to protect me from the Aunt Shirleys in this world instead of making me feel even more helpless and vulnerable.

I couldn't imagine two people less suited for each other than my parents. He was short, swarthy, bald. She was tall and pale, with thick, dyed blonde hair. She didn't approve of gambling. She complained about his personal hygiene. For good reason. He didn't shower on a regular basis, didn't

bother with deodorant. But his fingernails were immaculate. He had them done by a manicurist on First Street. Gamblers are fussy about their hands.

My dad wasn't always a gambler. He was born in a small village near Moscow and came to America in 1900 when he was about ten, along with his parents and his three younger sisters: lovely, intelligent, classy Anne; bitter, homely, spiteful Shirley; and coarse, flea-brained, sexy Rose. The Sharniks

settled in Cincinnati, Ohio, my mother's home. They even stayed with her family before they found a place of their own, and my mom was a bridesmaid at classy Anne's wedding to dapper John Keystone from Canada.

At thirteen, my dad displayed a remarkable facility for doing complicated math problems in his head, a talent which would serve him well in the mob. He quit school after third grade because he was bored, ridiculously out of place with all the eight year olds, and found a job in a factory making baseballs. I have a picture of him sitting behind a loom, looking like one of the street kids from “The Bowery Boys.” That was the first of only two legitimate jobs he would have in his life. A few years after quitting school, he fell in with a gang of lowlifes and ne'er-do-wells who lured him across the bridge from Cincinnati to that den of iniquity known as Newport, Kentucky, where he fell in love for the first time. Her name? Farobank.

According to my mother, who heard it from my aunt Shirley, my father underwent a dramatic personality change after a business trip with his dad while in his teens. It seems his father had a mistress. Shades of “Death of a Salesman!” Shirley claimed that, after that trip, my father stopped talking and aged ten years. Then there's the story, which may or may not be true, about how my dad lost his hair at the tender age of eighteen. His sister, sexy Rose, was a leggy blonde who loved palling around with the boys. Prudish Irving disapproved. When Rose attempted to leave the house to meet her boyfriends, Irving barred the way, and a struggle ensued, during which she grabbed hold of his hair and literally snatched him bald. On the other hand, Grandma Sharnik insisted that her son's early hair loss was the result of a tongue operation when he was a baby. Nobody took her seriously.

I never met my grandfather, who died of stomach cancer a year before I was born, but my mother filled me in. He was tall, handsome, well built, articulate and a spiffy dresser. Ladies adored him. My mother often wondered aloud why he married my grandmother when she looked like a monkey and could barely speak in sentences. In all fairness to Grandma Sharnik, my aunt Ann told me she was a talented landscape painter who encouraged her children to appreciate the arts. Then again, Aunt Ann was lavish with her praise of all things Sharnik.

Sharnik, which should be Shornik but they messed up on Ellis Island--means harness maker in Russian, and was the occupation of many generations of Shornik men. As automobiles began to replace the horse and buggy, my grandfather began to look for a new profession, and eventually moved the

family from Cincinnati to Detroit to work for the Dodge brothers. After classy Anne and sexy Rose married, my grandparents and spiteful Shirley moved to Hollywood to pursue the American Dream. That dream took the form of a little nut stand tucked into a spacious driveway on Hollywood Blvd.,

across the street from Dupar's Cafeteria. Grandpa's roasted nuts became the talk of the town, beloved by movie stars and moguls. It is said that Shirley almost fainted when Errol Flynn stopped by for a bag of cashews; Grandma Sharnik told him he was so handsome he should be in the movies. The success of the nuts made it possible for the Sharniks to buy a little house on DeLongpre Ave. where Shirley planted trees and flowers in their tiny backyard, and began a lifetime obsession with parakeets, canaries and antique doorknobs. Irving, who had moved to California before them, was a

frequent visitor at their dinner table.

Eventually, Grandpa Sharnik entrusted his nuts to his wife and daughter and spent most his days philosophizing about life on the beautiful beaches of southern California, waiting until the ocean was cold as ice before plunging fearlessly into the waves. My mother said her father-in-law took to the

beaches because he couldn't stand to be around his wife. She also confided that Grandpa was a card carrying Communist, which thrilled me no end when I was a college student going through my wild-eyed radical phase. I was sad that I never knew my grandfather. I'd have loved to have sat on the beach listening to him talk about communism and capitalism and Arthur Miller.

After my grandfather died, Grandma Sharnik and spiteful Shirley bought a big store on the Boulevard and called it The Hollywood Nut Shop. Mother said they were the biggest nuts in the place. Shirley grew more and more bitter about being stuck taking care of her sickly mom while her sisters had

husbands and children and spent their days lounging around having tea and chocolates. When I was little, my mother would leave me at the nut shop while she shopped and did errands. I loved the rock candy, but Aunt Shirley scared me. I will never forget the time a lovely woman, beautifully dressed,

very refined, came in to buy a dried fruit gift package to send her husband who was overseas in the war. She asked Aunt Shirley about gift wrapping. Aunt Shirley's eyes burst into flame. WRAP IT YOURSELF! She was obviously jealous of this married woman whose brave husband was over there fighting the Nazis. Shirley thrust a role of white paper and some scotch tape at the woman. I expected her to leave without paying. To my dismay, she smiled, then did as she was told. I was shocked! I could be afraid of Aunt Shirley, I was just a little kid, but this was a grownup, and not just any grownup but a beautiful lady in movie star clothes. She should have had the wherewithal to protect me from the Aunt Shirleys in this world instead of making me feel even more helpless and vulnerable.

Years later, when my grandmother and aunt had sold the business and settled into a safe, dull, lonely existence on DeLongpre Ave., Shirley met a man, a Russian immigrant who had made a fortune in the Texas oil industry. A widower. His niece, a close friend of the Sharnik's, introduced them. He took her to restaurants, movies, art museums. Shirley laughed, she sang to her parakeet, she danced around the house. She was nice to everyone! The only problem was Grandma Sharnik. The old woman told Shirley she was crazy. Love, at her age? And when Shirley's suitor proposed marriage, and offeredto take her back to his ranch in Texas where they would build a little house for her mother, Grandma Sharnik said she wouldn't go. Thrilled for their sister, Anne and Rose advised her to go, they would talk to their mother, she would come around. Shirley accepted his proposal. When her fiance returned to his niece's house he told her the good news. In the morning, he didn't appear at the breakfast table at the usual time. His niece knocked at his door. There was no answer.

I may have hated Aunt Shirley when I was a child, with good reason, but the story of her lover's death broke my heart.

I may have hated Aunt Shirley when I was a child, with good reason, but the story of her lover's death broke my heart.

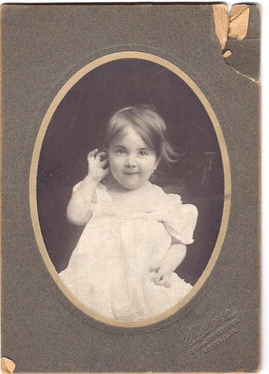

Sara as a baby around 1901

My mother, Sara Ruth Abrams, was born in Louisville, Ky., and grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. She had six brothers, one of whom died as an infant. Her mother, Rebecca Kanter Abrams, was often sick with “female problems,” so it

was up to her father to raise the children. At one point, my grandfather, who worked long hours at a factory, could no longer care for the children and was forced to put them in an orphanage where they were separated, and fed daily doses of loathsome concoctions for no apparent reason but sheer cruelty.

My grandparents met on the boat that took them to America. My grandfather came from Russia. Rebecca's Lithuanian parents looked down on Russians. But

their book-loving daughter loved her Russian peasant boy the moment she laid eyes on him. My mom described her uneducated father as a good-natured, funny, born storyteller who had little respect for schooling. He didn't

think education led to making a living. My grandmother, on the other hand, was proud of her high school diploma and insisted that her children take their schoolwork seriously. She didn’t have to encourage her boys, especially Lou, her science whiz kid, who skipped four grades and graduated from high school at the top of his class. Lawyer Harry, Math marvel Max and Doctor Nathan were also high achievers. Lazy Manny and Silly Sara, were not.

In truth, Sara was a gifted writer. She often earned pocket money writing essays for her schoolmates. In response to endless praise for her older brothers she became the class clown. It was she who pinned the sign “KICK ME HARD” on the back of her teacher's apron. As such, her father was forever pleading with her teachers to take his prankster daughter back. He pretended to be upset, but on some level she knew he was proud of her. After high school, Grandpa Abrams tried to talk his sons into working for his businessman brother in Louisville, Ky., but they worked their way through

college. Their father called them educated fools. Though her brothers offered to pay for college, Sara chose to live with her parents and work as a crack typist for the government, which was to come in handy when her father was laid off during the Depression.

My mother was not a hit with boys. It could have been that she was a prude who carried “walking home” money in her shoe in case a date tried to squeeze her privates. More likely, it was coming from a family of high achieving boys. Sara wasn't expected to excel. She was expected to crochet, and

embroider, and cook, while her brothers were at Hebrew school or playing baseball. Sara wished that she'd been born male. Her own mother made it clear that she preferred her sons to her only daughter, and found poor Sara to be rather dull, and annoyingly self-pitying. It's not surprising that

Sara found herself an old maid in her early thirties.

was up to her father to raise the children. At one point, my grandfather, who worked long hours at a factory, could no longer care for the children and was forced to put them in an orphanage where they were separated, and fed daily doses of loathsome concoctions for no apparent reason but sheer cruelty.

My grandparents met on the boat that took them to America. My grandfather came from Russia. Rebecca's Lithuanian parents looked down on Russians. But

their book-loving daughter loved her Russian peasant boy the moment she laid eyes on him. My mom described her uneducated father as a good-natured, funny, born storyteller who had little respect for schooling. He didn't

think education led to making a living. My grandmother, on the other hand, was proud of her high school diploma and insisted that her children take their schoolwork seriously. She didn’t have to encourage her boys, especially Lou, her science whiz kid, who skipped four grades and graduated from high school at the top of his class. Lawyer Harry, Math marvel Max and Doctor Nathan were also high achievers. Lazy Manny and Silly Sara, were not.

In truth, Sara was a gifted writer. She often earned pocket money writing essays for her schoolmates. In response to endless praise for her older brothers she became the class clown. It was she who pinned the sign “KICK ME HARD” on the back of her teacher's apron. As such, her father was forever pleading with her teachers to take his prankster daughter back. He pretended to be upset, but on some level she knew he was proud of her. After high school, Grandpa Abrams tried to talk his sons into working for his businessman brother in Louisville, Ky., but they worked their way through

college. Their father called them educated fools. Though her brothers offered to pay for college, Sara chose to live with her parents and work as a crack typist for the government, which was to come in handy when her father was laid off during the Depression.

My mother was not a hit with boys. It could have been that she was a prude who carried “walking home” money in her shoe in case a date tried to squeeze her privates. More likely, it was coming from a family of high achieving boys. Sara wasn't expected to excel. She was expected to crochet, and

embroider, and cook, while her brothers were at Hebrew school or playing baseball. Sara wished that she'd been born male. Her own mother made it clear that she preferred her sons to her only daughter, and found poor Sara to be rather dull, and annoyingly self-pitying. It's not surprising that

Sara found herself an old maid in her early thirties.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed